Mortgage leverage: How households spark financial crises

- Macroprudential Policy

- Aug 6, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 18, 2025

Unlike traditional home loans issued by banks, mortgages are securitized debt instruments that may fall outside banking regulations.

This allows excessive leverage—the ratio of debt to net worth—to build up in the financial system, particularly among households.

Leverage becomes dangerous when asset prices (especially housing) fall, causing household net worth to shrink. This leads to a rapid rise in leverage and increases the risk of default.

What is a Mortgage?

A mortgage refers to a security backed by residential real estate debt. Rather than each homeowner issuing individual bonds, thousands of home loans are pooled together, securitized, and sold in tranches to investors. Unlike traditional bank loans, mortgage-backed securities (MBS) allow for funding without a bank acting as the primary lender. That’s why we distinguish between home loans and mortgages—the former stays on a bank’s balance sheet, the latter may not.

Banks don’t issue mortgages directly, but they can purchase mortgage securities. This matters because banks' balance sheets are regulated, while MBS activity may escape direct oversight. Bank loan leverage can be capped; mortgage leverage, however, is harder to control, especially when banks are only acting as investors, not originators.

What is Mortgage Leverage?

Leverage is the ratio of debt to equity. For households, equity means net worth: total assets minus liabilities. The higher a household’s net worth, the lower the risk of default. Even in job loss, they can service debt from their assets. But as leverage rises, their vulnerability increases—small shocks can render them insolvent.

Financial regulators have tried to limit leverage, particularly within banks. Capital adequacy requirements are designed to ensure that banks hold a minimum level of equity relative to risk-weighted assets. This is the inverse of leverage: if leverage is debt/net worth, capital adequacy is net worth/debt.

Shifting Leverage Outside the Banking Sector

Bank capital requirements didn’t reduce systemic leverage—they just pushed it elsewhere. Firms began issuing their own bonds, bypassing banks. In the housing market, mortgage securitization replaced traditional loans. This migration of credit from the regulated banking sector to the unregulated shadow banking system was a key driver of the 2008 global financial crisis.

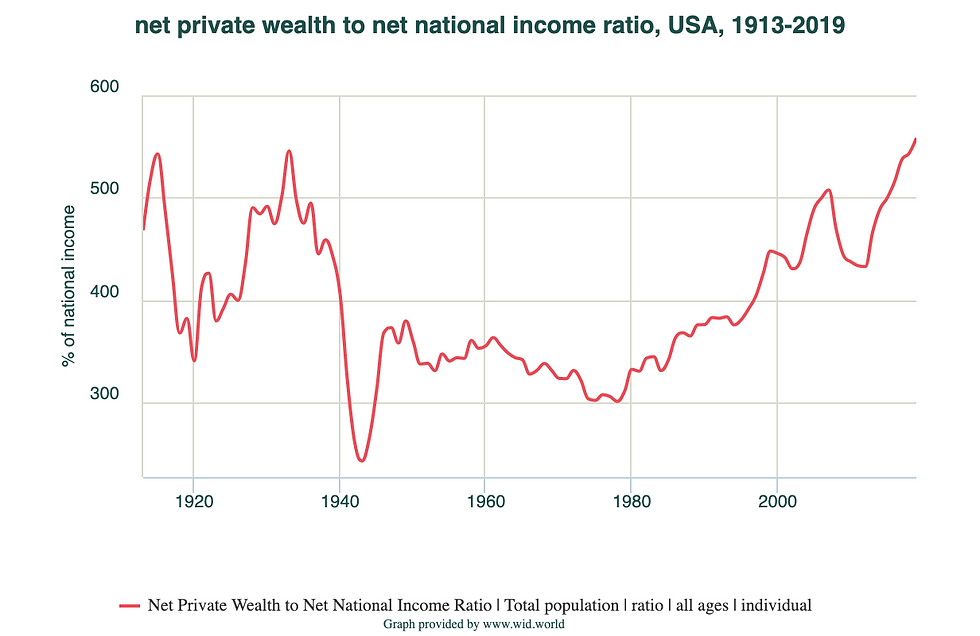

Between 1980 and 2007, U.S. private sector net worth surged relative to GDP. The sharp drop in this ratio due to the collapsing asset prices during the 2008 crisis marks the trigger point of systemic collapse. The graph below (source: Federal Reserve) shows the steep rise and fall in net private wealth relative to GDP.

Why Net Worth Matters More Than Debt

In leverage calculations, net worth is the denominator. While debt levels change slowly, net worth can collapse quickly—especially when asset prices crash. That’s why sharp drops in housing prices in 2008 triggered a wave of household insolvencies. It wasn’t just about high debt, but about evaporating net worth.

During the Great Depression and World War II, net worth relative to GDP was similarly depressed. 2008 was a reminder that private wealth is volatile—and when it falls, leverage explodes.

The Vicious Cycle of Falling Home Prices

Let’s say you buy a house with just 1% down payment. Your leverage is 100:1. A 1% drop in home prices wipes out your equity. As long as you're employed, you may keep up with mortgage payments. But if you lose your job and need to sell your house, you're underwater—and likely to default. That’s what happened in 2008.

Some borrowers defaulted even without losing jobs. These were speculative buyers betting on continued home price appreciation. They took loans with high monthly payments assuming they could sell the property within a year at a profit. When prices dropped, their model collapsed.

These foreclosures pushed prices down further, triggering more defaults—a downward spiral. As losses mounted, the financial system—already stretched thin on capital—began contracting credit. This hit not just households but businesses, deepening the economic contraction.

The Role of Financial Institutions

Financial institutions were exposed to mortgage risk in two main ways:

Insuring MBS (via credit default swaps or similar guarantees)

Holding MBS on their balance sheets

To chase yields, many invested in high-risk, low-rated tranches of mortgage securities. When defaults surged, these investments tanked.

A major casualty was Lehman Brothers. It wasn’t just that they lost money—it was that nobody trusted their liquidity position. Financial crises often begin as liquidity crises, where rumors and uncertainty prevent institutions from securing overnight funding. Lehman's leverage was so high that a relatively small drop in asset value wiped out its capital base.

Understanding Haircuts and Liquidity Traps

To borrow money, institutions post collateral. Lenders apply a “haircut”, demanding that the value of the collateral exceed the loan amount. When asset prices fall and rumors swirl, these haircuts increase. Institutions are forced to post more collateral—or face margin calls. In panic mode, there's no time for thorough asset valuation.

Imagine two financial institutions:

Financial institution A has $10 in equity and $50 in loans (leverage = 5)

Financial institution B has $10 in equity and $200 in loans (leverage = 20)

If each suffers a 5% loan default, A loses $2.5, while B loses $10—its entire capital. A survives; B collapses.

As fear spreads, even solvent institutions may be denied funding. Lehman failed not necessarily because it was insolvent, but because it was illiquid and untrusted.

Leverage: Not Just a Banking Problem

While financial institutions are often the epicenter, other sectors also pose risks. Households and businesses can carry hidden leverage through derivative exposures or overvalued assets. In 2008, it was households who collapsed first, then dragged down the rest.

Conclusion

High leverage turns small shocks into systemic crises. Mortgage markets amplify this risk by allowing borrowers to access credit with minimal equity. When home prices fall, net worth collapses, leverage surges, and credit freezes. If banks, businesses, or households are over-leveraged, financial stability is compromised.

Controlling leverage not just within banks, but across the broader economy—including households and shadow banks—is key to preventing future financial crises.

Comments